Driving home from the farm recently I heard Michael Pallin interviewed on CBC Radio 1 about his new book Erebus, which recounts the ill-fated attempt of the British Naval Captain Sir John Franklin and the 129 officers, scientists, and crew to find a Northwest Passage through the arctic sea in 1845.

Panel 4: Search for Franklin

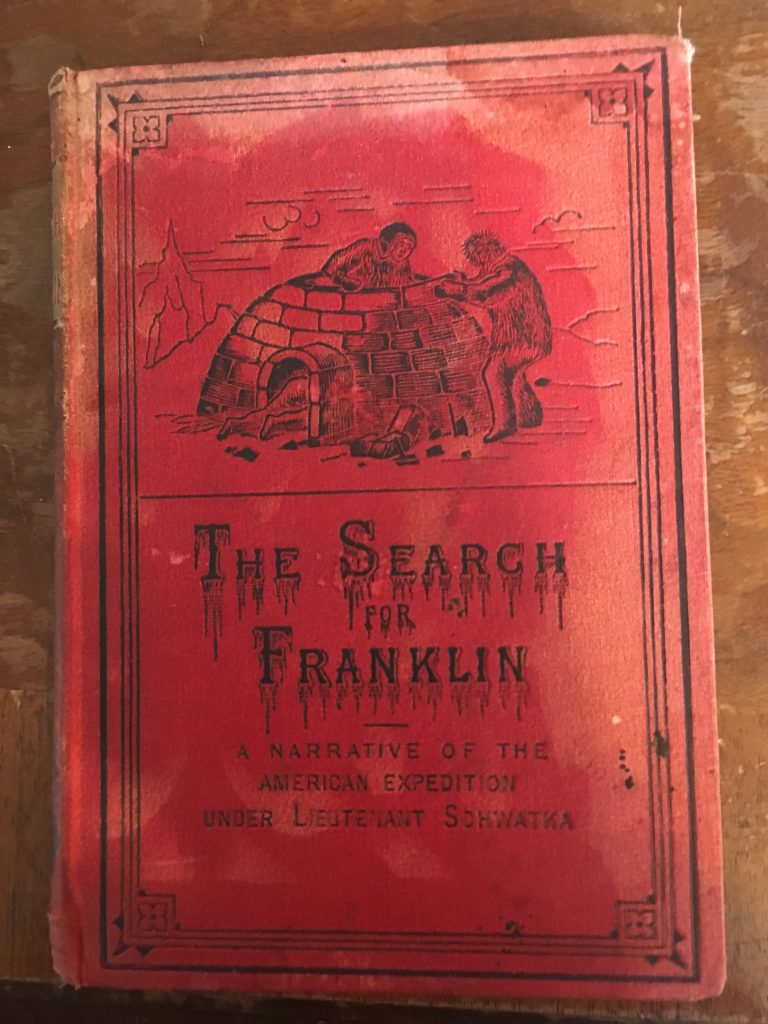

My long-standing intrigue with Europeans out of their depth in their early exploration of Canada was sparked enough that when I got home I went straight to our bookshelf in search of a title I’d held on to while clearing out my Dad’s library some years back. The Search for Franklin: A Narrative of the American Expedition Under Lieutenant Schwatka is one of those distinctively undersized volumes with ink-sketches typical of a 19th century library.

It recounts one of dozens of similar expeditions launched in the mid-to-late 1800s to piece together the fate of Franklin and his crew who were locked in ice for 16-months before abandoning ship and venturing across the frozen expanse in a quest for survival. None of them made it out alive.

Only a few pages into Schwatka’s account I was struck all over again by the pathos of the demise of Franklin’s officers and crew. In hindsight it seems obvious what would have kept these men alive as they staggered half-crazed across a foreboding and frozen landscape on which they had no bearings: accessing the indigenous knowledge base that was all around them!

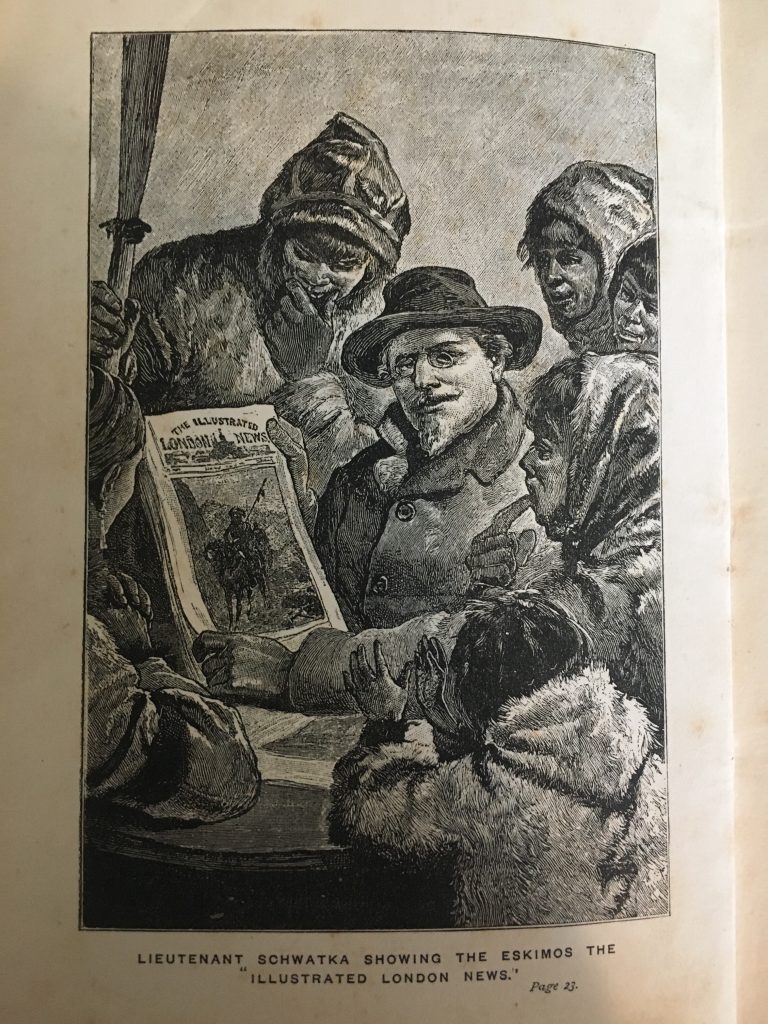

For his part Schwatka had the common good sense in his search for clues to interview the Inuit. Of course, they were the only potential witnesses to the last days of Franklin and his men.

One such witness was an Inuit woman by the name of Ahlangyah who recounts to Schwatka her firsthand encounter with “ten white men dragging a sledge with a boat on it.” She describes how she and her husband put up a tent near the white men “at the crack in the ice”. Apparently the two parties remained together for five days. “During this time the Inuit killed a number of seals which they gave to the white men.” Ahlangyah’s account goes on:

At the end of five days all started for Adelaide Peninsula, fearing that, if they longer delayed, the ice, being very soft, they would not be able to cross [to the mainland]; and they travelled at night when the sun was low, because the ice would then be a little frozen. The white men followed; but as they dragged their heavy sledge and boat, they could not move as rapidly as the Inuits, who halted and waited for them…

At the end of five days all started for Adelaide Peninsula, fearing that, if they longer delayed, the ice, being very soft, they would not be able to cross [to the mainland]; and they travelled at night when the sun was low, because the ice would then be a little frozen. The white men followed; but as they dragged their heavy sledge and boat, they could not move as rapidly as the Inuits, who halted and waited for them…

The white men they never saw again, though they waited at Gladman Point….In the following spring, when the ground was almost clear of snow, [Ahlangyah’s party] saw a tent standing on the shore at the head of Terror Bay. There were dead bodies in the tent, and outside lay some covered with sand. There was no flesh on them, nothing but the bones and clothes… Numerous articles were lying around such as knives, forks, spoons, watches, many books, clothing and blankets. (pp. 35-37)

Perhaps the word “stuff” didn’t exist back in the mid 1800s. Or perhaps the Inuit or the British press were too polite to point out the obvious. Either way, it seems clear that Franklin’s naval officers didn’t survive because they were dragging around too much of it.

I get that their boats must have held out for them a fast fading hope of making it back to England alive. But hauling Shakespeare across the tundra? And a full library of scientific tomes? To say nothing of silverware, watches (wouldn’t want to be late for high tea), and rank-confirming uniforms? In hindsight it seems like the full onset of madness.

One can’t help but wonder if the story might have been different if they had only found the courage to let go of the rope that dragged the sledge, that held the boat, that carried the stuff, that gave them the last vestiges of a sense of security. What if they had stopped clinging to their perceived identity and dared to trust that the Inuit could teach them a whole other way of living on the earth. Who knows? Schwatka might just have found a few survivors living among the Inuit who could have told him their tale in full.

I’m not one to point out the obvious but let it be noted that the parallels to our own time are painful. Our attachment to fossil-fuel derived comforts and consumption-driven economies all but rubber stamps our own demise and yet we carry on, dragging around a lifestyle that the earth is incapable of sustaining for 7.53 billion people and counting.

The Feather

This past fall I organized an event to raise money for RAVEN, an indigenous people’s legal defence fund, and as the evening wrapped up I was surprised to be presented with an eagle feather by Anishinabe land defender, Stacey Gallagher. I’m not sure why I was singled out for this honour. Perhaps because of the stand I took outside the gates of Kinder Morgan alongside other Tsleil Waututh allies, or perhaps because of my vocational commitment to nurturing spiritual resiliency in the lives of children and youth.

Regardless, I was humbled by the honour though, in truth, being a relative newcomer to indigenous spiritual practices, I wasn’t sure what to do with it. I knew if I asked Stacey he’d only say something like “You’ll know what you need to know when you need to know it.” Indigenous spiritual practices are not prescriptive in the same way that Christian practises are. He was dismissive when I thanked him for the feather: “I didn’t give it to you. The feather gave itself to you.”

When I got home I set the gift down on a cockleshell from Santiago de Compostela alongside a devotional book and  prayer stool from my own tradition. I then went on with the rest of my life and the feather stayed in place where I had set it.

prayer stool from my own tradition. I then went on with the rest of my life and the feather stayed in place where I had set it.

A month passed. Then two. When opportunities presented themselves I was careful to watch how eagle feathers were used in First Nations ceremony. I had never noticed before. In particular I observed how they were put to work during a smudge to fan the embers of the sage bundle and direct the movement of the smoke toward the person seeking cleansing.

Still, I thought, who am I to assume that role. It felt presumptuous.

One day I phoned Stacey and told him that I had yet to pick up the feather. He laughed (Lesson #1, Don’t take yourself too seriously!) then went on, his response typically indirect. “The eagle is a type of intermediary between earth-dwellers and the Creator. On the strength of his or her wings an eagle carries away the negative energy that we release from our bodies during a smudge.”

Stacey went on to explain how the person doing the smudge will often flick the feather at the end so that the negativity falls to the ground below. The earth, he continued, is capable of absorbing and dissipating our negative energy. A type of spiritual recycling program! “This is how generous our Mother is. She looks after us in every way.”

This was for me an awakening experience, i.e. what in other contexts I would call an “aha” moment. It was like being put in touch with a truth buried deep inside me that chose this moment to reveal itself. Suddenly many things fell into place…. including my cows.

The Givingest of Creatures

For the past three years I’ve spent my (very) early mornings in the company of a herd of dairy cows where I am one of the milkers on the farm. I know the cows well. Each has a name (Sweet Pea and Jean and Tilly to name a few) and recognized personality traits. I’m sure they say the same about us milkers. The point is, I am comfortable in their company as they are in mine.

So here’s the thing. On more mornings than not I’ll start off my dairy routine carrying a lot of negative energy from my life outside of the farm, i.e. worry over whether my daughter will pass Grade 11 pre-calculus or my son will make the basketball team, a heaviness over harsh words exchanged the night before with my husband, dread at the thought of an upcoming work commitment I’m not prepared for, panic over whether we’ll have enough money to make the loan transfers, and general malaise over whether I’m a credible human being or not. You know, the usual stuff.

Then this happens: over the 3 hours that I’m in the company of the cows – rounding them up, scratching their backs, chatting with them (Me: “Did you know that in India cows are considered deities?” Cows: “What?! Really?! No fair?!”), massaging their udders and pre-stripping their teats to stimulate let down – over that span of time my heavy spirit dissipates. And more often than not a sense of inexplicable gratitude, and at times a giddy gladness, rises in its place.

I’ve often wondered at that transformation, and now, after my conversation with Stacey, I understood this exchange for what it was. The cows absorb my negativity and in so doing lay bare my own inner sense of grounding and goodness. I don’t know how else to explain it. The dark clouds of fear and self-doubt and inadequacy and dread are taken from me simply by being in the presence of these givingest of creatures.

This revealed a new dimension of how the earth is caregiver. Up until that point I had primarily understood the earth “as mother” to be about the resources she provides to sustain our physical needs (food, air, fire etc.). Now I saw how the natural world in mystery and silence cares for us spiritually and mentally as well – how the trees absorb our anxiety and how rivers carry our sorrow, how eagles bear away our pain and how ordinary dairy cows hold our ambiguities without judgement.

In my last post I proposed a creed for a low-bar spirituality . One of the tenants of the creed is “I’m an earth-dweller and so are you”. I see now that I hardly know what this means. The world’s First Peoples are the most credible earth-dwellers and the climate crisis has brought the rest of us (on our knees!) to their storehouses of knowledge.

While the temptation will be to pillage and plunder (after all plundering seems to be in our DNA) their nearly-forgotten but now essential earth-dwelling wisdom, the invitation is to listen with hearts open. In my experience, the hoarding of such knowledge is not in their DNA.

My guess is that they will put us to work letting go of those ropes which we are clinging to so desperately in an attempt to haul our lifeboats across the landscape, giving us a false sense of security while all the while being led to our doom.

The Ancestors

My daughter to my surprise and without any prompting picked up the eagle feather the other day. It was after our big Father’s Day meal and we were lounging around in the living room doing some drumming and singing – a ukulele and spoons somewhere in the mix – when, with complete spontaneity yet full of respectful intention, Abigail stood up, walked over to my prayer shelf, lit some sage, lifted the feather and came around the room inviting us in turn to smudge.

My astonishment had as much to do with how naturally the act came to Abigail as with the beauty of the gesture itself. Abigail has a Cherokee grandmother in her paternal lineage whom we know almost nothing about. Maybe it was this grandmother’s spirit that came to Abigail in that moment. Maybe the feather was given to me so that it could continue its journey onward into hands more receptive than my own.

Fantastic, Tama. So good. Thanks.

Glad it spoke to you Linnea. Thanks for saying so.

Thanks for these thoughts. Incidentally, I had dairy goats for a while when we lived in Kenya, and the ritual of milking was very calming, so I get your experience in the cow barn. and I’d say you are a credible person! = )

Cool about the goats. And now the silk worms. I’m sure that most any engagement with the natural world bears away our life-sized sorrows.

Thanks Tama… I am amazed at the way yoru mind and spirit wander through the layers of history and truth and sad fact/fiction, all with an eye to Creator and Mother Nature. I’m grateful that our circle of life has at least a little intersection.

The older I get the more I see how interconnected everything is, which means no shortage of writing material!

Thank you Tama, that was beautiful. It’s truth is making me teary!

Thanks Sandra. I consider you among those who knows how to hold a feather, both in defiance and in solace.